Today in History: A Lincoln Pardon (And, You Know, That Whole Surrender at Appomattox Thing)

Major & Knapp Print, Library of Congress.

On April 12, 1865, Generals Ulysses S. Grant and Robert E. Lee met, and Lee formally accepted the surrender terms drawn up on April 9th, and disbanded the Army of Northern Virginia. Several small battles took place after Lee's surrender, but the war was effectively over. For thousands of troops, the fighting was now done.

George Maynard's Letter to His Uncle. From the Compiled Military Service Records, US National Archives

For one Union soldier, however, this date held even more significance. Private George A. Maynard of the 46th New York Infantry was arrested September 18, 1864, as a deserter, only 15 days after enlisting, and taken to Fort Monroe. He was charged with the even more serious crime of deserting to join the opposition. At trial, Maynard was found guilty on February 14, 1865, and sentenced "to be hung by the neck until dead."

Telegraph from Lincoln to Grant, Dated February 23, 1865. From the Compiled Military Service Records, US National Archives

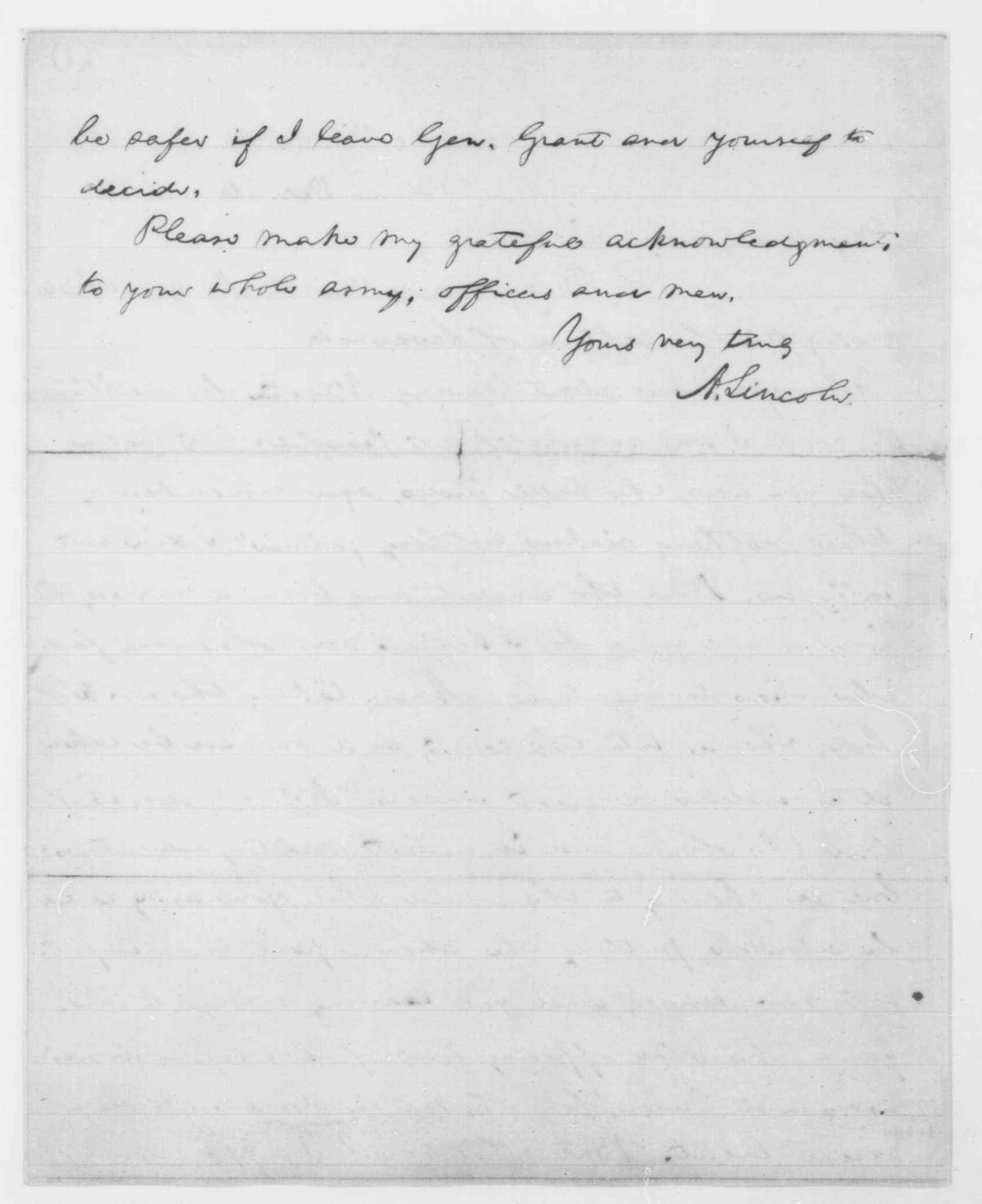

The soldier sent a message to his uncle, Harrison Maynard, of St. Albans, VT, entreating for help. Uncle Harrison must have been well connected, because less than ten days later on February 23rd, President Abraham Lincoln telegraphed General Grant, ordering him to suspend Maynard's sentence until his case could be further reviewed. Lincoln, in spite of the Herculean burden of running a country at war with itself, reviewed the cases of hundreds of individual soldiers, converting sentences and pardoning many. Entreaties on behalf of soldiers came from those in high positions of power--governors, congressmen--and regular, everyday people, if they could get their request to him. The President treated each request, once received, the same. Lincoln's mercy became a sore subject with his Secretary of War, Edwin Stanton, who wished the President would remember that the Army needed harsh consequences at times to keep the troops in line.

On April 12, 1865, Lincoln officially pardoned George A. Maynard, and ordered he be returned to his regiment. Two days later, Lincoln would be assassinated by John Wilkes Booth; so Maynard was lucky in more ways than one. The official order pardoning Maynard was published on April 24th, and sent out to General George G. Meade and the Army of the Potomac. Meade in turn sent the order back, explaining that the 46th New York Infantry was no longer serving with his outfit. Maynard finally returned to his regiment on June 5, 1865, and was mustered out with the rest of the 46th at the end of July. We'd call his army tenure a short, but storied career.